6 min read | May 15 2024

Lending helps people achieve their goals, whether that is to redo their kitchen or buy a new dishwasher.

It enriches day-to-day life, drives economic growth, and powers progress — providing you lend responsibly; that is, to people who can (and will!) pay you back.

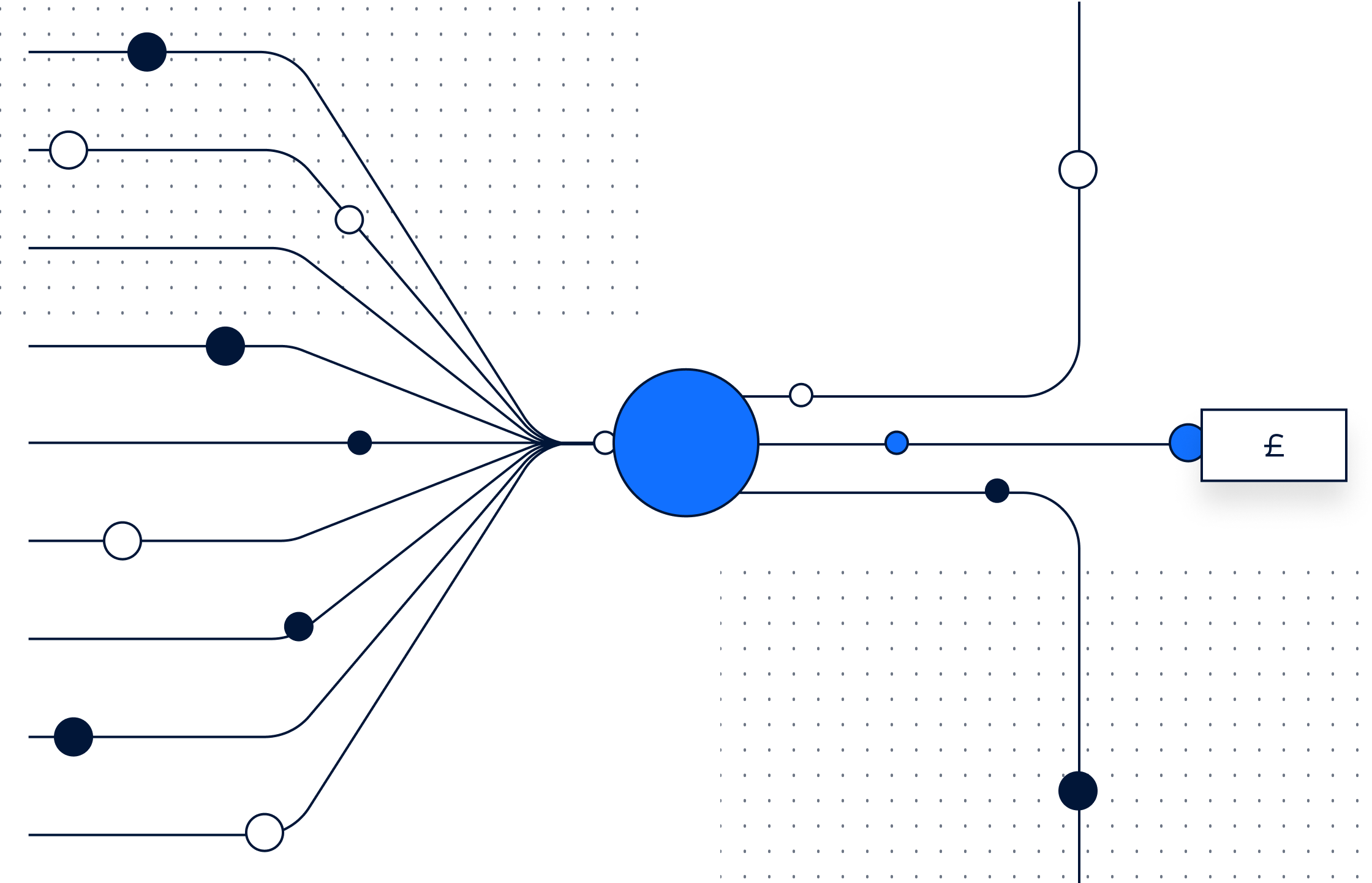

Today, this poses UK lenders with a £29bn monthly question: how can you accurately assess if someone is able and willing to pay back their loan?

Today’s credit information markets have matured to play a significant role in the lending industry. However, there are still challenges we as an industry face. In the words of Chris Woolard: “The market is not working as well as it could ...[in]... delivering the best possible outcomes for consumers and lenders.”

In the recently released Final Report into the Credit Information Market Study the FCA stated, “A well-functioning credit market helps protect consumers, improve consumer outcomes and increase market efficiency.”

While their report found the market was working in places, they felt the need to propose a broad set of remedies that would make it work effectively for consumers and lenders.

At Infact, we are delighted to be supporting the CIMS work as a member of the FCA’s Interim Working Group reforming SCOR. We’re on a mission to resolve key deficiencies highlighted in CIMS and increase responsible lending through the sharing of higher-quality credit information between lenders in a more timely way. But to understand where we’re going, we need to understand where we came from.

The bureaus as we know them were each the product of their unique circumstances, but there’s a common pattern to each origin story:

- 1. Evolving economic environment breeding a new breakthrough in consumer product,

- 2. regulatory inflexion points pursuant to market changes, and

- 3. underlying technical innovations that enable the change.

As we prepare to enter the next era of credit referencing, let’s look at where it all began.

1899: The birth of Equifax

It’s 1899, the tail-end of the industrial revolution in the US. The country is growing richer as reliance on agriculture tapers off and workforces move into factories.

One day, there’s a knock at the door.

Two men named Cator and Guy Woolford want to know if your customers are 'Prompt' or 'Slow' to pay you. They're establishing the first traditional credit reference agency (CRA).

In other words, you’ve just had a visit from the team that will become Equifax.

Many of their measures were subjective, such as character references and lifestyle choices, but they changed the game by being the first to structure their data.

Unlike others at the time, they employed consistent notation of quantitative habits, along with sharing income and credit repayment history and records of unpaid bills.

By being one of the first to do so, their business was a success. And after noticing that insurance companies were among their biggest spenders, they soon expanded into specific data for life insurance in 1901.

Even in its infancy, Equifax’s earliest purpose was the same as that of CRAs today: to allow financial services providers to make decisions consistently and reliably, even if the process was very manual!

1967 - 1990+: Credit cards and the computerisation of data

Economic growth exploded in the post-World War II era, and consumer demand for credit products rose with it. Suddenly, solutions like mail-order and products like credit cards were taking off.

Enter Barclays.

Barclaycard launched in 1967, ushering in an era of sustained competitive growth in readily accessible consumer credit.

For the first time ever, consumers had access to a revolving line of credit that could be used anywhere, by anyone.

Naturally, people loved being able to be more flexible with their finances, and the mass consumer credit market was a huge success. But as more people signed up for credit cards, it wasn’t long before the volume of data generated outstripped the capabilities of manual record-keeping, and the industry needed a more efficient way to handle it.

Thankfully, advances in computing were happening fast, and a certain savvy bureau was particularly well placed to leverage this.

It was around this time, and with a backdrop of rapid technological progress, that Experian was born (albeit under a different name).

Consumer credit was becoming more widely available through credit cards, mail-order, and unsecured lending, and Experian UK quickly noticed an opportunity to help lenders make smarter, faster decisions. As such, they began formalising a credit referencing service about consumers of mail-order catalogue credit.

They soon expanded to collect information about other forms of credit and payment histories, including credit card companies, banks, and subsequently public records, eventually creating the first electronic consumer credit reports — or, as we know them, credit scores.

Scores aimed to provide an automated assessment of a person's creditworthiness based on the available information from a given bureau.

Between the deregulation of the banks in 1971 and the introduction of the Consumer Credit Act (CCA) in 1974, the economic environment was ripe for an innovative way to make lending decisions both easier and more responsible, so their timing couldn’t have been better.

Though credit scoring had been around in some form since the late 1950s, Experian took the UK by storm with its Credit Account Information Sharing database, securing almost two thirds of the UK credit information market by the mid-1980s.

1990s - 2000s:

The democratisation of lending

By the 1990s, the limitations of traditional credit scoring models had created a gaping hole in the market: the sub-prime sector.

The established bureaus were leaving a growing portion of the population underserved via exclusionary lending practices. If your credit score had slipped below prime for any reason, getting a traditional loan from a bank felt impossible.

But where there’s an underserved customer group, someone will step in to lend to them somehow. So non-bank lenders started offering short-term, high-interest loans to high-risk borrowers, and thus, the payday loan was born.

With legacy standards of credit information sharing, this was risky. But UK challenger CRA Callcredit was founded in 2000 with a new way of evaluating affordability data: they helped assess whether someone could pay, rather than just whether they would pay, by establishing the CATO data consortium.

They adapted their credit reporting system and offered tailored solutions to allow payday lenders to make better-informed lending decisions by sharing their data more quickly.

By facilitating faster data sharing between lenders, they were able to protect vulnerable customers and improve outcomes across the UK lending market. This was only possible through technical improvements in underlying infrastructure and the emergence of a newer lending product that needed a better credit referencing service similar to what we see in today’s market.

2001 – 2023:

Incredible change in Consumer Credit with little material change in Credit Referencing

While a number of “niche” Challenger CRAs have been established, like Credit Kudos, Crediva , GBG, and our friends at AperiData , the incumbent Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion have dominated an increasingly stagnant market with limited innovation on the fringes and increasingly legacy technology.

2010s - beyond:

Proper growth of digital lenders

As you have seen, CRAs are only really created when there are shifts in the consumer credit market and the subsequent regulatory inflexion points to maintain pace with those market innovations. Whilst CRAs are B2B organisation they only exist to serve consumer demand for credit and financial services. As demand patterns change with consumer adoption the CRAs have failed to meaningfully maintain pace with the change in the markets that they serve.

It’s 2023, and despite the data provided by CRAs staying the same, reliance on traditional credit scores is dwindling as the shift to faster, smarter, more dynamic, transactional lending accelerates.

Change is already underway, with nearly a third (32%) of all banks using AI technologies such as predictive analytics to make decisions in 2020 and 72% of UK financial services firms using machine learning as of 2022. However, these technical capabilities at businesses trying to leverage data to create the best outcomes for themselves and their customers are not being matched with new sources of credit related information. Innovations such as Open Banking have helped, but a gap in the market remains.

And with the government set to modernise the CCA in line with the FCA’s Consumer Duty there’s a clear blueprint of expectations around consumer responsibility, making new technology easier and safer to adopt when the time comes.

With the credit score emerging in the middle of the twentieth century (See the most epic blog on the FICO Score by Alex Johnson) to try and level the playing field on analytics and good debtor discovery, lenders are no longer reliant on ‘central’ CRA scores to outcompete the market in customer acquisition.

From our perspective, we are faced with a similar confluence of economic, regulatory, product, and technological change that has historically seen the bureaus we know emerge:

- The digital economy is growing faster than ever, with the rise of online shopping leading to Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) emerging as the fastest-growing credit product in modern history.

- Analytics are becoming more advanced every day, and AI is delivering exponential opportunities.

- Lenders are increasingly moving towards using raw, detailed data beyond traditional credit scores, while CRAs fail to improve the core data they capture.

- Larger numbers of consumers are being left underserved by traditional lenders, similar to the early 2000s.

- In a recessionary environment where circumstances can change quickly, the cost-of-living crisis is increasing arrears and financial uncertainty, so timely insights are required.

So we are in a time of deep innovation in the consumer credit market, of unparalleled pace of product ownership, as customers use more digital financial services for specific activities in their lives. We also have analytical headcount growing exponentially in financial services firms, when firms have more control over their digital journeys, data, and analytics stacks.

The question remains - where is the bureau to support them and to make the most of the products they offer for the consumers who want to use them?

What do we bring to the table?

At Infact, we are fascinated by the credit industry's evolution and how CRAs have enabled data sharing — but also the limitations of the available data.

It is through this lens that we see an opportunity to build on existing technological breakthroughs. We aim to embed modern credit and alternative data sources into the lending industry in real-time, protecting both consumers and lenders while driving financial inclusion.

We take heart in the FCA’s CIMS remedies pointing towards the deficiencies we set out to resolve.

However, with the cost of living crisis showing no signs of abating, the prime customer segment is being compressed. As a consequence, the financially fragile and underserved population consists of 20 million consumers in the UK alone, and roughly 1.7bn people financial excluded worldwide. Borrowers are increasingly squeezed out, with a shocking three million people borrowing from illegal money lenders in just the last three years.

With better, faster, and richer data sharing, more customers will be able to safely access responsible, affordable financial services.

That’s why we started Infact.

Thank you to everyone who has helped us get here so far.

*

Infact is Authorised and Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority as a Credit Reference Provider and is committed to continuing to innovate and deliver in the consumer credit information market.

Infact Systems Limited (“Infact”) is registered in England and Wales (company number 14032664), at 2-7 Clerkenwell Green, London, EC1R 0DE. Infact is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FRN: 978629)

Other articles you may be interested in

2 min read | Sep 30 2025

3 min read | Apr 02 2025

8 min read | Sep 20 2024